Tag Archive for: IFIs

In the framework of the public consultation process on the review of IDB environmental and social safeguards policies, together with a group of more than 50 civil society organizations in the region, we made comments and observations on the draft of the new Policy Framework. Environmental and Social, through a document that was sent to the Bank on Monday, April 20.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

The proposal of this policy differs from the previous ones, since this draft Framework seeks to integrate environmental and social policies into a single policy. Thus, the draft of the MPAS is structured in two parts. In the first, it presents the Policy Statement that addresses the IDB’s responsibilities and roles and relevant issues such as human rights, gender equality, non-discrimination and inclusion, rights of Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendants and other traditional peoples, participation of interested parties. , reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and protection of Biodiversity, and natural resources and ecosystem.

In the second part of the draft, the ten environmental and social performance standards that must be met by the borrowers throughout the project life cycle are detailed. In addition, for the Bank, the Standards will serve as guides for risk assessment, classification, due diligence, monitoring and management.

The 10 Performance Standards are as follows:

- Assessment and management of environmental and social risks and impacts.

- Work and working conditions.

- Efficiency in the use of resources and prevention of contamination.

- Community health and safety.

- Land acquisition and resettlement.

- Conservation of biodiversity and sustainable management of natural resources.

- Indigenous villages.

- Cultural heritage.

- Gender equality.

- Stakeholder Participation and Disclosure of Information.

Following the Bank’s Public Consultation Plan, the public consultation process on the MPAS began in January through face-to-face consultations scheduled by the IDB in different parts of the world. It was not only possible to participate through face-to-face consultations, virtual consultations were also enabled through the sending of comments through the Bank’s website or through an e-mail address. This first phase of virtual consultations ended on April 20.

It was in this framework that more than 50 civil society organizations that we have been working collaboratively and jointly since last year, prepared and sent to the IDB a document with a large number of comments and observations on the draft of the new MPAS.

The document, with more than 80 pages, is structured in general comments and specific comments on each performance standard found in the framework, and not only identifies in detail each of the problematic aspects that we identified in the draft, but also provides particular recommendations to correct them. In this way, it seeks to avoid the evident dilution of environmental, social and human rights standards that would entail the approval of the draft of the new MPAS as it stands. The document was sent on Monday, April 20, the date on which the first phase of virtual public consultations on the draft of the new MPAS ended.

At the same time, from Fundeps, and with the support and collaboration of a group of civil society organizations specialized in gender issues, we sent particular comments regarding the draft MPAS from a gender perspective. In this document, we raise the need for the IDB not only to avoid weakening its current Gender Policy, considered one of the most advanced in the matter in relation to the rest of the IDB-related Financial Institutions, but also to decide to put itself decisively at the forefront In this matter, for which it must necessarily carry out a process of mainstreaming the gender perspective in all its financed policies and projects (See document).

Which are the next steps? The IDB will prepare a second draft of the MPAS in which it must incorporate the recommendations and observations received from civil society during the consultation process. However, previous experience in recent consultation processes carried out by the IDB shows that the Bank is unlikely to incorporate and take into account the most important recommendations provided by civil society. We hope that in this case this trend will be reversed.

When the Executive Board approves the second draft, the IDB will publish it on its website and begin the second stage of the consultation process, which will be virtual and for a period of 30 days. Once this period has ended, it will produce the final version of the Framework and a document with the response to the comments received. The approved MPAS would take effect in January 2021.

From civil society, we hope that the IDB will take into consideration the comments and observations that have been made not only to avoid dilution of the institution’s social and environmental standards, which have been built together with civil society in recent decades. , but also to take advantage of the opportunity to advance and strengthen them. Something that becomes even more necessary in a regional context marked by the weakening of the national socio-environmental framework in most countries.

More information

- Public consultations on the IDB’s new environmental and social policy begin – Fundeps

- Draft Environmental and Social Policy Framework (MPAS) – IDB

- We participate in consultations of the new IDB Environmental and Social Policy Framework – Fundeps

- MPAS Policy Profile – IDB

- Additional Information on the Draft Framework for Environmental and Social Policy (MPAS)

- Evaluation of IDB Environmental and Social Standards – Office of Evaluation and Oversight

- Recommendations and comments on the draft of the Social and Environmental Policy Framework (MPAS) proposed by the IDB – Civil Society Organizations

Contact

Gonzalo Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

From Fundeps, together with the participation of some international civil society organizations, we sent the IDB a document with comments and observations on the Environmental and Social Policy Framework from a gender perspective.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

In December 2019, the Inter-American Development Bank -IDB- published the draft of the Environmental and Social Policy Framework (MPAS) in order to modernize its environmental and social policies. What does this MPAS mean? These are the requirements in environmental and social policy that the Bank or the Bank’s borrowers must meet when carrying out a project. In this statement, the Bank maintains a commitment to environmental and social sustainability, translated into a series of requirements and recommendations ordered in ten Performance Standards to be met in each project.

In January 2020, on-site and virtual public consultations began, in which Fundeps participated by presenting a review of what was proposed in social and environmental safeguards policies. This month, we led a document with specific comments and observations to Rule 9, on Gender Equality, and its lack of mainstreaming towards the rest of the MPAS Rules. This document was formulated together with another group of NGOs that adhered to the recommendations and together it was presented to the IDB. This work involved analyzing the entire draft of the Framework from a gender perspective and also contrasting it with previous gender policies published by the Bank.

As mentioned, the first shortcoming identified is the loss of mainstreaming of gender policy in project financing requirements. Taking into account that such projects directly and indirectly affect local communities, we demand that the Gender Equality Standard dialogue with other approaches such as race, ethnicity, class, age, religion, profession / activities, geographic location, among others. In other words, we demand that the problems be addressed from an intersectional vision, recognizing the coexistence of different vulnerabilities.

Regarding its conceptualization of gender equality, some inequalities of women with respect to men are mentioned, along with possible violence against trans people, so its approach in relation to LGBTTTIQ + people is scarce and superficial. Although it refers to ‘gender empowerment’ instead of ‘women empowerment’, there is no specific mention of gender, which manifests the reproduction of a binary, exclusive and regressive approach in terms of human rights. Furthermore, this means -not specifically mentioning the genres- the lack of incorporation of LGBTTTIQ people in the requirements to be met by the projects.

In its implementation measures, we note that the approaches proposed by the international human rights treaties for girls, adolescents, women, and LGBTTTIQ + people are not incorporated. On the other hand, the implementation measures required of borrowers do not include a proactive policy to advance on gender equality, as it was included in previous Bank gender policies. We continue with a preventive policy, although we identified an absence of a gender perspective in the design of strategies to mitigate and prevent violence, discrimination and inequalities.

In order to materialize progress regarding human rights in IDB-financed projects, we raise the need to strengthen the Bank’s commitment to the gender perspective, such as incorporating it at the internal level of its organizational structure. Taking into account the Bank’s ability to generate public policies through its choice of financing, we conclude that it must develop robust frameworks, operational policies, and accountability mechanisms that incorporate the gender perspective cross-sectionally and ensure the informed participation of affected people at all stages of all projects financed and undertaken by the Bank.

More information

- Comments and observations on the draft IDB Environmental and Social Policy Framework from a Gender perspective – Fundeps

- We participate in consultations of the new IDB Environmental and Social Policy Framework – Fundeps

- Public consultations on the IDB’s new environmental and social policy begin – Fundeps

- Observations on the draft of the IDB Invest Environmental and Social Sustainability Policy from a sensitive perspective on gender – Fundeps

- Draft Environmental and Social Policy Framework (MPAS) – IDB

- Gender and Diversity – IDB

Author

Mariel Pastor

Contact

Cecilia Bustos Moreschi, cecilia.bustos.moreschi@fundeps.org

Gonzalo Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

This document makes comments and observations on the draft of the IDB’s new Environmental and Social Policy Framework from a gender perspective. The comments and suggestions have been made with the aim of strengthening the Bank’s commitment to the gender perspective and its internal incorporation into its organizational structure. It also seeks to avoid the continued violation and corrosion of the rights of women and LGBTTTQ + people.

In the framework of the process of reviewing the environmental and social policies of the Inter-American Development Bank, we participated in public consultations held in the cities of Buenos Aires and Washington DC. Together with a group of civil society organizations, we raised certain concerns and recommendations regarding the review and consultation process, as well as the content of the draft of the proposed Environmental and Social Policy Framework.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

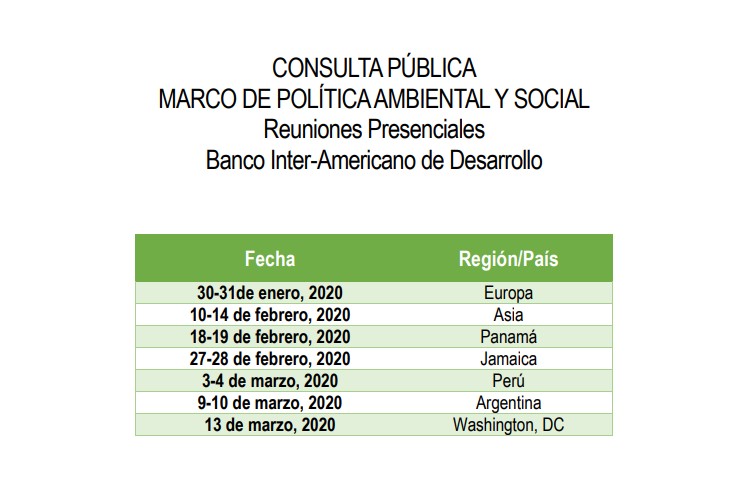

In January, the IDB began the public consultation process on a new Environmental and Social Policy Framework (MPAS), which has included, up to now, face-to-face and virtual consultations in the cities of Brussels (Belgium), City of Panama (Panama), Kingston (Jamaica), Lima (Peru), Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Washington DC (United States). In addition, the reception of a first round of virtual comments regarding the draft is contemplated until April 20.

From Fundeps, we participated both in the face-to-face public consultation carried out on March 10 in the City of Buenos Aires and in the consultation carried out on March 13 in the city of Washington DC. In turn, we plan to send written comments regarding the draft released by the Bank in the framework of a joint work we have been carrying out with a group of civil society organizations in the region.

In general terms, the draft MPAS proposes two different sections: a Policy Statement that basically establishes the roles and responsibilities that will correspond to the IDB in terms of compliance with the socio-environmental provisions and requirements of the new Framework; and a second section that includes the detail of the Environmental and Social Performance Standards with which the borrowers must comply. The draft proposes the inclusion of ten Standards: 1. Assessment and management of environmental and social risks and impacts; 2. Work and working conditions; 3. Efficiency in the use of resources and pollution prevention; 4. Community health and safety; 5. Land acquisition and resettlement; 6. Conservation of biodiversity and sustainable management of natural resources; 7. Indigenous peoples; 8. Cultural heritage; 9. Gender equality; and 10. Stakeholder participation and disclosure of information.

The IDB has argued that the proposed MPAS is based on five guiding principles: the non-dilution of current policies; results orientation (that is, effective implementation); the proportionality of the responsibilities and the established requirements regarding the level of risk of the project; transparency and the idea of ”doing good” beyond “doing no harm”.

However, the analysis that we have carried out together with the rest of the organizations involved in this process allows us to glimpse that, at least as proposed, the current draft is far from effectively complying with each of these guiding principles. In general terms, a dilution of policies and socio-environmental protection can be seen in many of the Performance Standards; it is not clear how effective the implementation of said MPAS will be; The idea of proportionality is not reflected in many sections of the draft; and practically no sections can be identified in the draft that propose “doing good” in the sense that the Bank proposes: that of facilitating more sustainable social and environmental results.

In turn, the entire review process being carried out by the Bank is far from being transparent and “offering significant opportunities for participation by all interested parties” as established by the IDB. Precisely, as usually happens with the consultation processes carried out by the IDB, this process has had important shortcomings, especially in the objective of achieving effective participation by stakeholders.

We have duly expressed all these criticisms and problems to the Bank’s representatives in each of the consultations in which we participate and we accompany them with specific recommendations and suggestions that they should take into account when preparing the next draft of the Framework. In addition, these recommendations will be sent in writing in advance before the expiration of the term to send comments virtually.

Having completed the public consultations and once the period for receiving comments and suggestions virtually ends, the Bank must prepare a new draft of the Environmental and Social Policy Framework to be presented to the Board of Directors. Subsequently, the new Draft will be published for a new round of virtual comments for a period of 30 days, according to the Public Consultation Plan approved by the Bank’s Executive Board. Upon completion of this period, the IDB will develop the final version of the Framework that will be submitted to the Policy and Evaluation Committee of the IDB Board for final evaluation.

The IDB is a member of the IDB Group. It is a source of long-term financing for the economic, social, and institutional development of Latin America and the Caribbean and, unlike IDB Invest that invests in private sector projects, the IDB is responsible for investment in the public sector.

More information

-

Public consultations begin on the new IDB environmental and social policy – Fundeps

-

The IDB and the IDB Invest review their environmental and social policies – Fundeps

- Environment policy and safeguard compliance (2006) – IDB

-

Modernization of the IDB’s environmental and social policies

- Policy Profile – Modernization of IDB Environmental and Social Policies

Contact

Gonzalo Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

This working document addresses one of the new multilateral development banks: the New Development Bank (NDB) of the BRICS. It develops its beginnings, structure, policies and strategies, the projects it has underway and the role that China has in the Bank.

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) began the process of public consultations on the new Framework for Environmental and Social Policy. It will have both face-to-face and virtual instances and will be extended throughout the year 2020.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

With a statement on its website, the IDB announced the start of virtual and face-to-face public consultations on the draft of the new framework for environmental and social policy. According to the bank, this new framework aims to strengthen the environmental and social sustainability of the bank’s operations and, in turn, be more effective in responding to the challenges faced by the countries of the region to achieve the long-awaited growth. sustainable.

The Environmental and Social Policy Framework contemplates safeguards policies, lessons learned and good practices accumulated over the years. In addition, the policy mentions the bank’s commitment to environmental and social sustainability, and the 10 performance standards that borrowing member countries must meet.

Also, the draft policy contemplates environmental and social risks and impacts and highlights advances in human rights, gender equality, non-discrimination and stakeholder participation.

According to the consultation plan approved by the IDB Executive Board, the public consultation process will be significant, inclusive and transparent. However, a large part of civil society that has been working on agendas linked to the IDB over the last few years doubt that this is really the case, being guided by the bad experiences of the most recent public consultations carried out by the institution, which They characterized by their shortcomings in terms of public participation and transparency.

In-person consultation processes will take place at the Bank Headquarters in Washington D.C. and in some countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Asia. Those interested in participating in face-to-face consultations may do so by registering here.

On the other hand, those who want to participate in virtual consultations, can send comments on the draft of the new policy through the website www.iadb.org/es/mpas or by sending an email to bid-mpas@iadb.org. The first phase of comments can be made until April 17.

Why is it important to participate?

For several reasons, it is necessary that civil society, citizens and, above all, indigenous communities and communities affected or potentially affected by IDB or IDB Invest operations actively participate in this process, contributing their experience and its recommendations and suggestions regarding the environmental and social safeguards of the institutions.

First, because both the IDB and the IDB Invest are, today and despite the diversification of financial actors operating in the region, key actors in financing for development in Latin America and the Caribbean. According to the Bank itself: in 2018, with a historical amount of US $ 17,000 million approvals, the IDB and the IDB Invest were consolidated as the main source of multilateral financing for Latin America and the Caribbean. The IDB approved a total of 96 sovereign guaranteed loan projects for a total financing of more than US $ 13.4 billion, and disbursed more than US $ 9.9 billion. In turn, 2018 was a record year for IDB Invest, with approvals of US $ 4,000 million, 26% more in volume and 21% more in number of transactions than the previous year. The IDB Invest extended its support to sectors such as infrastructure and Fintech, adding to education, tourism, water and sanitation, transport and energy. In the case of Argentina, the IDB has historically been the main multilateral partner for the country’s development, with an average of recent annual approvals of US $ 1,360 million. The current active portfolio with the public sector is 54 operations for an approved amount of US $ 9,206.4 million and an unpaid balance of US $ 3,874.7 million, according to the information provided by the Bank itself.

Second, because a robust and effective system of environmental and social safeguards is key to avoiding the impacts at the socio-environmental level that, in many cases, bring infrastructure projects financed by institutions such as the IDB or the IDB Invest. When the design, application or implementation of environmental and social safeguards fails in these types of projects, the impacts and consequences especially in the communities involved are often complex, and unfortunately in many cases, irreversible. Cases such as Camisea in Peru or Hidroituango in Colombia reflect the bitter consequences of the bad, or even the lack of application of socio-environmental safeguards in projects financed by the IDB Group.

Third, because an active, informed, responsible and coordinated participation by the key actors of civil society and the indigenous and affected communities of the region would contribute to the objective of avoiding a possible (and latent) dilution of the system of environmental and social safeguards from both the IDB and the IDB Invest. Recent experiences of dilution of environmental and social regulatory frameworks after review and “modernization” processes not only in related institutions such as the World Bank or the International Finance Corporation (IFC), but also in the national regulatory systems of the countries of The region clearly reflects a trend that the IDB Group seems not to want to escape.

Sofia Brocanelli

Gonzalo Roza

Gonzalo Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

The ICIM, accountability mechanism of the IDB and IDB Invest, on the occasion of increased reprisals towards applicants, has worked to improve the capacity of its team in dealing with these situations. Consequently, it has developed a series of Guidelines to address the risk of reprisals in the management of applications that will take effect in 2020.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

The IDB and the IDB Invest have an accountability mechanism (IAMs), the Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism, better known as ICIM.

The accountability mechanisms have been created by the IFIs so that communities can file claims against possible damages that have been caused by the investments that banks make and, therefore, that are not complying with environmental, social standards and transparency according to which the institutions carry out their work. The characteristics of this type of mechanisms are adapted to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, specifically its pillar 3 of access to reparation mechanisms by victims.

However, it has been frequently observed that applicants who file complaints in the ICIM suffer from reprisals, manifested in various ways. This does not cease to endanger the life of the applicants, who in most cases are environmental and / or human rights defenders. In 2018, the mechanism observed an increase in cases where confidentiality is requested for fear of reprisals or acts of intimidation towards the communities in which the Bank-financed project is being developed.

For this reason, the ICIM developed the toolkit ‘Guide for IAMs on measures to address the risk of retaliation in claims management’. This guide aims to assess the level of risk that would involve the intervention of a mechanism and what are the ways to prevent, mitigate, reduce or address it. In both sections, the document provides tools to guide the mechanisms and their respective institutions on what steps should be taken to address these situations.

In Latin America, environmental and human rights defenders suffer constant violations of their rights. For this reason, and in order for financial institutions to become more aware of this problem, the mechanism met with the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The central conclusion of this meeting was to ratify the centrality that human rights should occupy in financing for sustainable development. As a result, the ICIM, starting in 2020, will have the ‘Guidelines to address the risk of retaliation in the management of applications’.

The Guidelines have been created so that applicants, given the risk of reprisals before or after making a complaint before the mechanism, can effectively apply the MICI-IDB and MICI-IIC Policies. They constitute a tool to implement in regions or areas where there is simply the risk of retaliation.

The Guidelines will be used according to factors that create, increase or aggravate the risk of retaliation by applicants before the Mechanism; It is also intended to work with applicants to reduce and address the risk factors that are identified.

The guidelines document addresses the principles for case management where retaliation risk is detected. Some of these principles are:

- Zero tolerance for retaliation,

- Participatory and continuous risk assessment;

- Action without damage;

Honesty and transparency about the ICIM mandate on reprisals.

The guidelines should serve as a guide to train the entire work team in Retaliation Risk Management, disseminate the guidelines and provide training to other IDB Group units. In addition, it makes the document available for any institution to use, provided they do not alter its content.

Finally, the guidelines will have to be shared with applicants at the registration stage to analyze the existence of retaliation risk. If so, an ICIM team must prepare a Retaliation Risk Analysis (ARR). According to the level of risk identified in the analysis, the Mechanism team will develop a Joint Plan to reduce retaliation risk (PCRR) that may establish prevention or mitigation measures.

If these guidelines are applied correctly, it would mean an advance in the protection of environmental and human rights defenders, as well as communities, who make claims due to the negative social and environmental impacts of projects financed by international financial institutions.

More information

- Independent Consultation and Research Mechanism – ICIM

- Brochure: The Independent Consultation and Research Mechanism (ICIM) – Fundeps (2015)

Author

Sofia Brocanelli

Contact

Gonzalo Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

This document aims to bring observations and comments to the draft of the new Environmental and Social Sustainability Policy of the IDB Invest. These observations are made with the objective of making visible conflicts and problematic problems in the IDB Invest.

This document aims to present the observations and comments to the draft of IDB Invest’s new Environmental and Social Sustainability Policy from a gender perspective, which is practically absent in the current draft. These observations are made with the aim of making conflicts and existing problems in the actions of IDB Invest more visible, related to the violation of rights, inequality, violence and the sexual division of labour, first and foremost.

Since the creation of the World Bank (WB) in 1944, with the aim of facilitating and promoting reconstruction and post-war development, the purpose of the institution has been changing over time, adapting to new realities and international contexts . Today, on its 75th anniversary and positioned as “one of the main sources of financing for the eradication of poverty through an inclusive and sustainable globalization process,” the Bank has new challenges that include, among other things, its framework of relationship with civil society, which although it has been strengthening in recent decades, still has huge outstanding issues.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”.

Over time, the reformulation of the World Bank’s purpose brought new institutional practices, including the incorporation of civil society as a valid counterpart not only in relation to the internal governance of the institution but also as a party consulted at the time of planning the projects.

Thus, as a result of the growing closeness of the work areas of the World Bank and of many Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), as well as the deep commitment of an increasingly organized civil society, the Bank began to open, little by little. , new ways of participation and involvement of CSOs both in the construction of policies and in the administration of projects.

In this way, there has been a paradigm shift, which went from being institutionally focused and merely consultative to a model that works in conjunction with CSOs, focused on specific issues. For example, their more active participation in the elaboration of the Strategies of Assistance to the Countries (EAP) and the documents of strategies to fight against poverty, among others.

On the other hand, many CSOs have also changed their position regarding the World Bank’s role in society and have decided to work in an articulated manner. The majority of CSOs that interact with the Bank are currently adopting an “positive intervention” approach, which aims to influence the Bank’s decisions; rather than adopt an essentially confrontational position. Even so, it should be clarified that a large part of civil society maintains its critical and supervisory stance vis-à-vis the World Bank projects, especially in relation to those Bank-financed infrastructure projects that have major socio-environmental impacts.

The strengthening of the dialogue between civil society and the World Bank has been reflected both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, for example, with the increasing active participation of CSOs in the Annual and Spring Meetings organized by the Bank, and in the increase in policy dialogue sessions within the framework of the Forum on Policies related to Civil Society (which it was organized for the first time in 2009 where 300 representatives of civil society organizations from more than 30 countries participated). In turn, qualitatively the spectrum of participation was broadened by bringing different sectors such as youth associations and also incorporating agenda items such as food security and health, among others.

It should also be noted that, in order to promote this strengthening in a transversal way to the entire institution, the World Bank has coordinated efforts with the International Development Association and other members of the World Bank Group, such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which provides political risk insurance for projects in various sectors of countries, developing members and the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), an institution responsible for arbitrating a solution to disputes between governments and nationals of other states that have invested in that country.

In this way, it can be seen that in the course of the last decades and as a consequence of a greater openness on the part of the institution, but more than anything due to the increasing pressure and demand coming from civil society, demanding greater participation in decisions and Bank actions, a process of strengthening relations between the World Bank and civil society has been evidenced. However, there are still important shortcomings and issues still to be resolved in the relationships of these actors, which is currently reflected in the disagreement of a large number of CSOs regarding the Bank’s actions in a series of related agendas, especially to the protection of the environment and human rights, and the responsibility of the institution in this regard.

The revision of the Environmental and Social Framework of the World Bank and the criticisms of civil society

Precisely, one of the most recent criticisms of the World Bank from civil society has been the recent revision of the Institutional Environmental and Social Framework and what much of civil society considers as a clear weakening or dilution of the safeguards framework and social and environmental standards of the institution. The reasons for this weakening follows a trend at global, regional and national levels and responds to the need to make the Bank more competitive, in an international context of loss of competitiveness vis-à-vis other emerging financial actors.

Thus, for example, the Comparative Analysis of the regulations of the International Financial Institutions present in Latin America carried out by the Regional Group on Financing and Infrastructure (GREFI) of which Fundeps is a part, highlights the way in which World Bank investments have been recently made less competitive against new emerging actors such as the Development Bank of China, for example. Likewise, the report carries out a comparative analysis where it can be seen that environmental and social standards turn out to be more lax in emerging financial actors, which to a large extent allows them to become the first sources of financing for National States, displacing traditional institutions such as the World Bank or the IDB, which have more robust standards and, therefore, imply greater costs and delays for national governments.

Given this situation of loss of competitiveness by the World Bank, the Bank’s Social and Environmental Framework recently reviewed and in force in 2019 is considered by some civil society organizations as flexible against some fundamental issues that would put the environment and rights at risk Humans from the villages of the member countries. For their part, CSOs have expressed reservations about the review of safeguards that practically did not take into account their recommendations. Also, CSOs have denounced that the new MAS lacks a human rights approach and does not take any reference of international standards in the matter.

On the other hand, the main criticism towards the work of the World Bank, regarding this context of competitiveness, is the exclusion of due diligence by the bank by granting the possibility to borrowing governments to request to use their own safeguards systems to national level transferring responsibility for the correct application of safeguards to governments and not to the bank.

In this way, it can be concluded that the World Bank faces great challenges as a financial institution to remain competitive in the face of new emerging institutions and, in turn, incorporate the demands of civil society effectively and effectively. Thus, improving the relationship of real participation with civil society in an increasingly complex context, without weakening its socio-environmental regulatory frameworks, continues to be a latent challenge for the World Bank within its 75 years.

More information

New analysis on regulations in development institutions present in Latin America – Fundeps

Authors

Ailin Toso

Florence Harmitton

Contact Gonzalo

Roza, gon.roza@fundeps.org

The purpose of this document is to describe the operation of the Green Climate Fund, where its financial resources, its projects, operational policies come from and how its accountability mechanism works.