Supported by public health organizations from across the region, FUNDEPS files a complaint against the Arcor campaign “Your fair share” with the Ombudsman for Children and Adolescents.

In mid-September of this year, Arcor launched the advertising campaign called “Your fair share” which states that “a healthy life is a balanced life in which to take a liking and take care of health go hand in hand.” In this way, a green front label with the phrase “Your fair share” was stamped on several products of the company, indicating “what is the recommended daily portion of what you like and it does you good”.

These types of messages have been criticized by public health specialists for being deceitful and risky, and for contradicting recommendations of human rights organizations and public health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization ( OPS). Commercial strategies of this kind in practice promote products with high concentrations of critical nutrients (sodium, sugar, fats) whose regular consumption has a harmful effect on health. In fact, Argentina leads the rates of childhood obesity in Latin America.

This commercial strategy violates the right to health and food for children and adolescents. That is why we decided to make a complaint to the Ombudsman for the Rights of Children and Adolescents of the Province of Córdoba, as a public body in charge of protecting the rights of these groups. Our presentation asks:

- that the means to respond to Arcor’s advertising campaign “Your Fair Share” be determined for the impact on the rights to health and food of children and adolescents;

- that mechanisms be put in place for the dissemination of correct and scientific information on healthy eating and in particular regarding this campaign;

- that the Executive and Legislative Power of the Province be urged to strengthen the regulatory framework to prevent commercial actions such as this one from being carried out, which violate the right to health and food of children and adolescents.

Argentina’s current regulations related to food labeling and marketing techniques are ineffective in adequately protecting the right to health and food, which leaves room for companies to take advantage of these legal gaps, confuse consumers and consumers, and limit their choices.

In this way, the State fails to comply with its obligation to protect the human right to health, which requires that the actions of third parties not affect the effective enjoyment of the right to health of a group of people. This implies a violation of human rights obligations as long as the State fails to comply with the recommendations of monitoring bodies on how to deal with the obesity epidemic. Different organs and specialized offices such as the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Committee on the Rights of the Child or the Rapporteurs for the right to health or the right to food have marked that the epidemic of obesity is definitely a human rights problem.

This situation demonstrates the need to strengthen the existing regulation and the implementation of effective mechanisms aimed at restricting these deceptive marketing practices and preparing a nutritional label that provides the necessary information to ensure the right of consumers and consumers to clear and truthful information, contributing to the choice of healthier options.

Furthermore, considering that this marketing strategy does not facilitate access to information, it directly targets children and generates confusion about critical aspects of these products, since FUNDEPS is investigating a possible violation of the legal framework of consumer protection. This could imply a breach of the company’s duty to provide adequate and accurate information, and the prohibition of misleading advertising, affecting the right to health and healthy eating of consumers, fundamentally in children and adolescents

Beyond these considerations on the need to improve the current regulatory framework and on an eventual violation of consumer protection regulations, the presentation before the Ombudsman’s Office aims to limit a strategy that affects the rights to health and nutrition. boys and girls. In this sense, Juan Carballo, Executive Director of FUNDEPS, argues that this proposal seeks that an agency in charge of looking after the interests of children and adolescents, pay special attention to a campaign that affects their rights. “We hope that Arcor can be aligned with the practices recommended by specialized health agencies. In addition, in this way it would not fall into a double standard depending on the country in which its products are sold ”

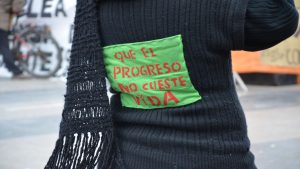

While in Argentina the same product is promoted with the label “your fair measure”, in Chile it receives the triple warning of product “high in saturated fats”, “high in calories” and “high in sugars”:

Arguments against the campaign:

- The campaign promotes ultra-processed foods in the context of health emergency due to the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in NNyA

- The campaign uses deceptive marketing techniques

- The campaign puts the health of children and adolescents at risk

- The campaign emphasizes individual responsibility

- The campaign violates the right to information of consumers

- The campaign is presented in products of “small portions” and not for 100 grams

- The campaign is based only on calories

Adhere:

- Dirección General de Enfermedades Crónicas No Transmisibles – Ministerio de Salud de la Provincia de Córdoba

- Coalición Latinoamérica Saludable (CLAS)

- Fundación Interamericana del Corazón y sus afiliadas en México, Argentina, Bolivia y Caribe

- CISPAN Centro de Investigaciones Sobre Problemáticas Alimentarias Nutricionales (UBA), Argentina

- IFMSA (International Federation of Medical Students Associations) y su sede nacional de Argentina, IFMSA-Argentina

- Consumers International Latinoamérica

- ACT Promoción de la Salud, Brasil

- El Poder del Consumidor, México

- Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria, México

- Instituto de Investigaciones en Salud y Nutrición (ISYN), Quito, Ecuador

- Alianza para el Control de ECNT Chile

- Frente por un Chile Saludable

- Fundación EPES, Santiago, Chile

- Guillermo Paraje, Profesor titular de Economía, Escuela de Negocios, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez, Chile

- Alianza ENT-Uruguay

- Centro de Investigación para la Epidemia de Tabaquismo, CIET-Uruguay

- Asociación Uruguaya de Dietistas y Nutricionistas – Uruguay

- Instituto Nacional de Cáncer, Uruguay

- Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor – IDEC, Brasil

- FEMAMA, Porto Alegre, Brasil

- Educar Consumidores, Colombia

- Fundación Colombiana de Obesidad (FUNCOBES))

- Mesa por las ENT Colombia

- Corporate Accountability, Colombia

- Alianza ENT-Perú

- COLAT (Comisión Nacional Permanente de Lucha Antitabáquica). Perú

- ESPERANTRA (Asociación de Pacientes y Usuarios de Servicios de Salud de Perú)

- SLACOM Sociedad Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Oncología Médica

- Coalición México Salud-Hable, México

- Salud Crítica, México

- Contrapeso, México

- Public Health Institute

Contact:

Juan Martin Carballo – juanmcarballo@fundeps.org

Agustina Mozzoni – agustinamozzoni@fundeps.org