In Argentina, legislation and public policies on care have made progress but also obstacles. Within the framework of the International Day of Domestic Workers and the 8th anniversary of the enactment of Law 26,844 on the Special Regime of Work Contract for Personnel of Private Houses, we highlight the importance of the legislation and regulation of the work of those who they take care of it in a remunerated way, although we recognize that there is still a lot of hard work in pursuit of its effectiveness and expansion.

“Below, we offer a google translate version of the original article in Spanish. This translation may not be accurate but serves as a general presentation of the article. For more accurate information, please switch to the Spanish version of the website. In addition, feel free to directly contact in English the person mentioned at the bottom of this article with regards to this topic”

In the 1950s, the first laws related to domestic work appeared, in order to define labor relations and their rights as workers.

But it was not until 2013 when Law 26,844 was enacted, which established a special work contract regime for paid workers in private homes. This law regulates the labor relations that are established within private homes or in the sphere of family life and that do not generate a direct profit or economic benefit for the employer. It defines this work as any provision of cleaning, maintenance or other typical household activities services, personal assistance and accompaniment to family members or those who live in the same home with the employer, and the non-therapeutic care of sick or disabled people.

In this process, activism and later the union organization of private house workers, has been key in the fight for their rights. The Union of Auxiliary Personnel of Private Houses (UPACP), which encompasses the workers of private houses, “carries out its tasks of defense and representation of the workers in the sector since the beginning of the last century. Today the workers have a law that regulates the activity, No. 26,844, which equates, as appropriate, the work of domestic service to that of workers from other unions. Now the workers of private homes have the right to vacations, maternity leave, among all labor rights. ”

This law tries to put the rights of private house workers on an equal footing with those of any other worker in a formal and dependent relationship. However, the characteristics of domestic work, related to the private sphere, the invisible, with the duty assigned to women to care for and give love in a disinterested, selfless way and without any type or with little remuneration and recognition, It makes it difficult for these activities to be considered as work and those who perform it, as workers.

Labor market of private house workers

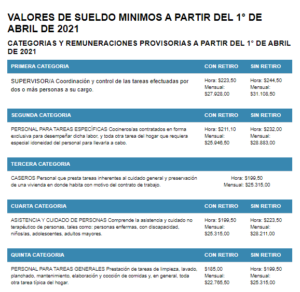

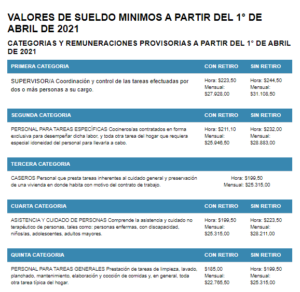

Law 26844 not only establishes the regime of private house workers but also different categories according to the type of work that was developed in the domestic sphere. These categories translate into salary scales:

www.upacp.org.ar

However, this recognition is far from meaning the realization of their labor rights.

According to a report by the National Directorate of Economy, Equality and Gender, in Argentina, the main occupation of women is paid domestic service: it represents 16.5% of the total employment of employed women and 21.5% of wage earners. It is the most feminized activity in the market (96.5% are women), the one with the highest informality rate (72.4%) and the one with the lowest average income in the market, constituting the poorest workers of the entire economy. This means that a domestic worker earns 46 pesos for every 100 that a private sector employee receives and 30 pesos for every 100 that a formal worker receives. Compared to men, they earn 26 pesos for every 100 pesos that one of them earns. According to the ILO, this informality and precariousness generates the breach of rights and a space for labor exploitation, even of girls and adolescents.

For Candelaria Botto: “In our country, where the State does not satisfy these needs, the role of domestic workers becomes essential for a large number of households. However, this work takes place mostly in precarious conditions and with low remuneration, which shows the little social value that is given to reproductive work. ”

Even with all these limitations on access to rights, it is likely that a registered employee, whose labor relations are regulated by a legal framework, is in better working conditions.

That the autonomy of some does not take it away from others

Now, who are the women that make up this group of domestic workers?

Mercedes D´Alessandro, in her book “Economía Femini (s) ta”, affirms that the “fairy godmothers” who sustain the lives of those who inhabit the households with the highest income are women in situations of vulnerability and poverty. Many of them have dependent children and most have not been able to complete secondary school (only 2% of them completed a tertiary degree or university). As a result, 40% of poor mothers are private house workers.

They are women who need to work but are not qualified to access other types of employment. In addition, it is usually one of the first job options for women from other countries, although the percentage of internal migrants among these workers is more remarkable. Many young women see this job as a way out of poverty, but end up living in a utility room of a wealthy family that does not pay them a Christmas bonus, vacation or sick days.

At this point, it is important to think about the tense link between paid and unpaid forms of care. Given the unjust social organization that distributes care, paid and unpaid care work falls mainly on women. That is why it is always necessary for a woman to take care of, to “free” another of these tasks. And here, it is not only the stubborn persistence of the sexual division of labor that undermines advances in favor of a more just and equitable society, but it is also other factors of inequality and oppression that overlap with gender. The class and powerful processes of racialization that still persist go through caregiving.

As domestic work is, to a great extent, carried out by poor women, peasants, migrants, representatives of various ethnic groups, with low education and little education, who find in this activity a means of subsistence, it is one of the most devalued jobs not only in economic terms but also in social terms. Thus, families with higher incomes can turn to the market to free up time, which implies hiring another, poorer woman to do domestic and care work.

As D’Alessandro says: “behind every great woman, there is another great woman.”

This invites us to think about care in a feminist and intersectional way, which puts care work at the center of the scene and de-romanticizes it. Because the lack of decent wages and real access to labor rights is not compensated with gratitude and love.

As Sol Minoldo says: “How feminist can a process be in which some women emancipate themselves at the expense of others, leaving the sexual distribution of domestic work intact?

If there is exploitation, it does not stop there because the worker is treated with affection and the trust of our intimate life is opened to her, although it may be noticed a little less. It is time to question the way in which “love” has been used to make it invisible that domestic work is work, whoever does it. That love is not an excuse to deny workers their rights. ”

Although the importance of care and of those who care – especially during the pandemic – has become increasingly visible, this has not yet translated into salary improvements in the case of paid domestic and care work. We still owe a debt to the people they care for. With domestic workers, there are still huge social, cultural and economic gaps to fill. They perform essential work but in precarious and irregular conditions, with miserable wages that are barely enough for them to access the basic food basket.The gaps and obstacles that these workers face every day are an impediment to real access to their rights as workers, as women and as people.

Author